Gutenberg Gold: Mike, by PG Wodehouse

In which a Substack is announced and we read through an early novel by PG Wodehouse

Not enough people know about the sheer range and vitality of free ebooks out there, and my new substack, Gutenberg Gold aims to spotlight some of the highlights that should be better known.

Every year, thousands of books fall into the public domain, meaning that they can be quoted, adapted, modified and most importantly, read, without paying any money to the authors estates.

Winnie the Pooh and Mickey Mouse have grabbed the headlines, but meanwhile every year, work by popular and readable authors like Agatha Christie, Thornton Wilder, PG Wodehouse and Franz Kafka is falling into the public domain and becoming available on online repositories like Project Gutenberg.

The big ebook publishers don’t want you to know this, however. Anything they can charge for an out of copyright book is pure profit for them. Why should you shell out for a classic edition, when Jane Austen, Charles Dickens and Charlotte Brontë are free on the net and can be imported to your ereader in a couple of clicks? Most of the Gutenberg files have better proofreading than the cheap online editions, and several contain beautifully digitised illustrations.

Each month, Gutenberg Gold will be reviewing a classic work, available absolutely free on the internet. Generally we’ll steer away from the most famous books in order to shine a light on neglected novels that will largely be new to you.

How easy is it to download these ebooks to your device? For many like me, it will be as easy as using the dedicated browser on your ereader to go to the Project Gutenberg website and download the appropriate file. You can also upload them to a device from a computer, share from an app or use services like Amazon’s Send to Kindle emails.

So without further ado, let’s talk about our first pick, an early school story by PG Wodehouse.

Mike, by PG Wodehouse

The school story has a strange half-life in British children’s literature. Inevitably structured around the boarders in a single-sex public school, these now read like insights into a totally alien life. Somehow, they stay compelling: I was state-educated all the way, but devoured the Malory Towers books and even sought out out-of-print series from the local library, like Jennings and Billy Bunter. In the comics, the Bash Street Kids went to something that was recognisably a comp, but Winker Watson in the Dandy was still a public schoolboy. Then, of course, the Harry Potter books brought common rooms, house points, school sports and sneaking around after dark firmly back into the mainstream of children’s literature.

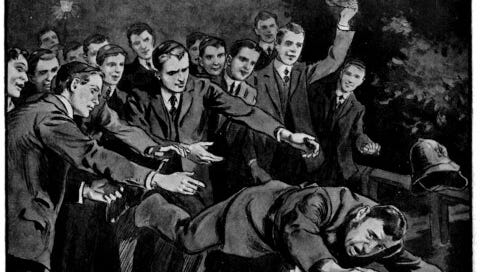

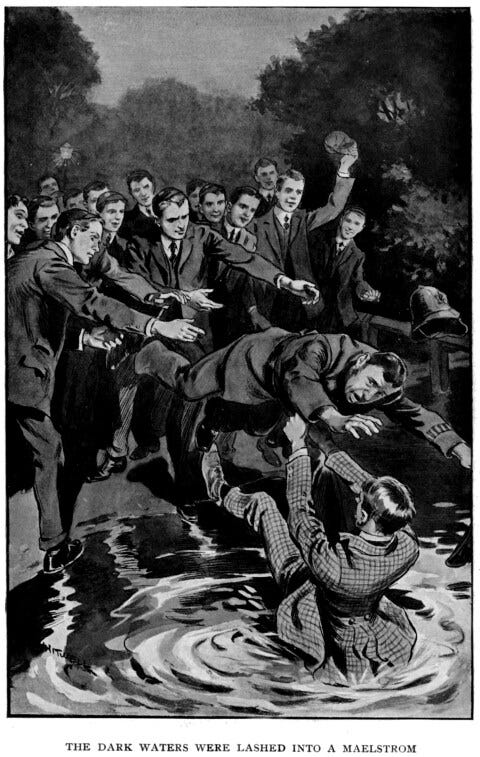

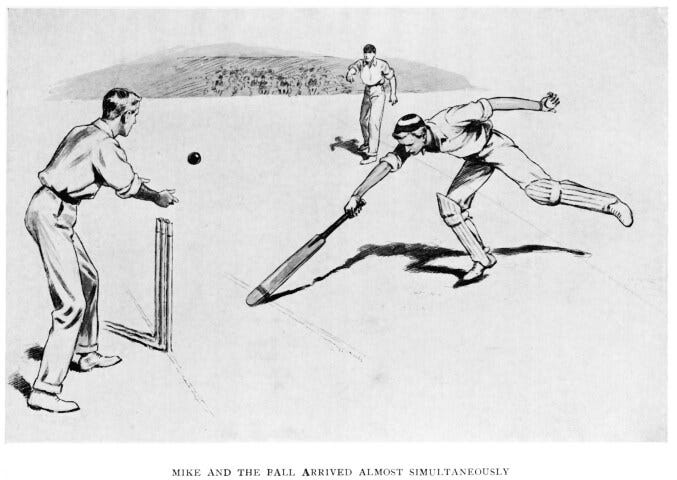

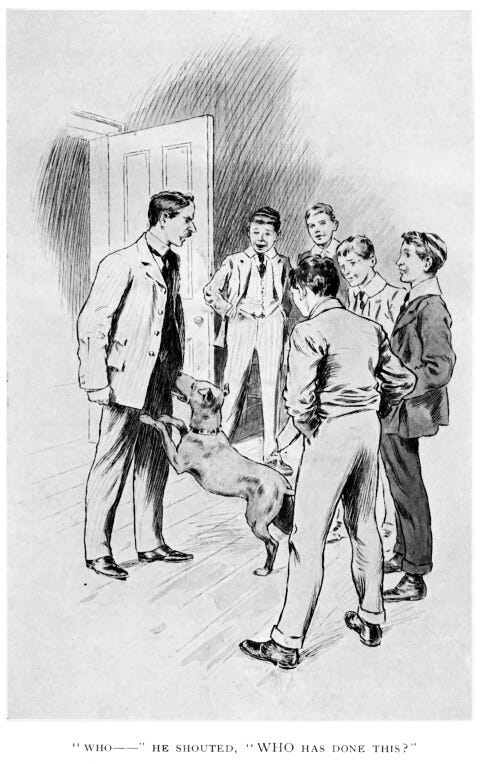

Which brings us to Mike, only the tenth novel ever published by PG Wodehouse, the light comedy titan of the twentieth century who created the world famous Jeeves and Wooster and Blandings series. George Orwell, no less, hailed this novel as ‘one of the best ‘light’ school stories in English’, though it was difficult to find even in Orwell’s time. It well repays a little curiousity. This Gutenberg edition contrains twelve charmingly of their time illustrations, but more importantly it serves as a kind of secret origin; the second half introduces Psmith, one of Wodehouse’s more memorable creations, who returns in classics of the canon like Psmith Journalist or Leave it to Psmith.

Psmith is a champagne socialist—a monocled, tophatted member of the upper classes who insists on calling everyone comrade and who never meets a higher authority without wanting to subvert it. Wodehouse would later claim that the character was based on a school acquaintance, Rupert D’Oyly Carte, but I think that this is something of a blind. Of all Wodehouse’s characters, Psmith and his sidekick Mike, the more-or-less forgettable character for which the book is named, are the most autobiographical.

The four Psmith novels follow path of PG Wodehouse’s life and developing writing career exactly. Mike deals with the happy schooldays that PG Wodehouse longed for and romanticised. Psmith in the City is a way of working through his unhappy period of working at a London bank, containing many true-to-life details and many delightful revenges upon obstructive superiors that Wodehouse must have daydreamed about himself. Psmith Journalist follows the characters to New York, a city Wodehouse loved deeply and where he saw his skills blossom. Finally, Leave it to Psmith closes the set by following Mike and Psmith to Blandings Castle, that happy scene of country-house farce that Wodehouse’s later novels never wandered very far from. You could write a biography of young PG Wodehouse, based around these four stories. You could call it In Psearch of Psmith

.

One downside for some will be the cricket. There is a vast deal of this, with one match memorably spanning two whole chapters. Even Wodehouse himself is minded to apologise wryly for the all the cricket, telling us ‘it was unavoidable’. Yet that’s part of the spell of the school story itself—despite not caring two figs for lacrosse, I used to lap up chapter after chapter of the stuff in the Malory Towers books. Dickens famously wrote an entire chapter about cricket in the Pickwick Papers without knowing the first thing about the game, and I put Mike aside feeling almost like I could repeat the feat. It’s a feature of the relative gentleness of the book that the chief drive of the first half is Mike’s aspiration to get into the first eleven. (The second half was published separately, and less patient readers can also find it on Gutenberg as Mike and Psmith.)

After this, the story leaps two years ahead and switches schools, after Mike’s stinking school report in every subject but cricket spurs the paterfamilias to move him to a school whose lower sporting reputation is balanced by its academic honours. Mike, in a fit of dudgeon, refuses to splay for this lesser school, instead getting into a series of minor escapades with his new friend Psmith, an ex-Etonian who finds himself in a similar predicament.

How gently the engines of storytelling used to putter along in those bygone days! You couldn’t write something like this now without throwing in a sexual awakening, dead parent trauma or evil wizards. Here, the worst that happens is that the housemasters dog is painted red.

.The style and the face, however, remain pure Wodehouse. There’s a brief, horribly dated moment where a racial slur drops into conversation out of nowhere, but that aside it’s a novel that can be enjoyed by any fan of Wodehouse, classic children’s fiction, or comic writing more generally.